I made this kimchi

While traveling, it is occasionally fun to hear remarks that you may have made to a visitor to your own country — call it “conversational karma”. In my case, it came from being warned repeatedly that this dish or that morsel might be “too spicy”, and to beware. This has never made me not think of the kid glove treatment I give people who come to Thailand, which no one has ever associated with chilies or spicy food before, no siree.

Ogling Korean-style hot dogs at Lotte World

Like the Thais, Koreans came into contact with chilies in the 1600s, courtesy of the seafaring Portuguese. And like the Thais, Koreans have taken to chilies with a vengeance. There is rarely something adorning the dinner table that is not slathered in some kind of chili sauce, ready to be cooked and wrapped in greenery of some kind, a handy food delivery system in lieu of those sadistic metal chopsticks that Koreans like to use. If it’s never come into contact with chili before, no worries, they have it covered. I learned this the hard way when I went to Krispy Kreme for the first of what would be many times (I have a 7-year-old) and ordered the “hot original”. No, the “hot original” is not a glazed doughnut hot from the oven. It is a doughnut flavored with kimchi spices and then glazed. This would explain its bright orange color and the bits of scallion that appear to float on the surface of the dough. For once, it was indeed “too spicy”. My son was not a fan.

But it was summer, and many other delights awaited us. For example, the chilled buckwheat (and sometimes corn!) noodles, a great relief to this particular Glutton allergic to most other types of flour:

Chilled buckwheat noodles with shaved ice, hard-boiled egg and cold nashi pear

This was a great relief at mealtimes because the weather was so stultifyingly hot, it made me actually miss Bangkok. It felt like walking around inside of a microwave. Needless to say, it was murder on everyone around me, as I had chosen the occasion of this trip to start experimenting with natural deodorants. I spent the week oscillating between “orange alert” (smelling like ketchup) and “red alert” (lamb souvlaki).

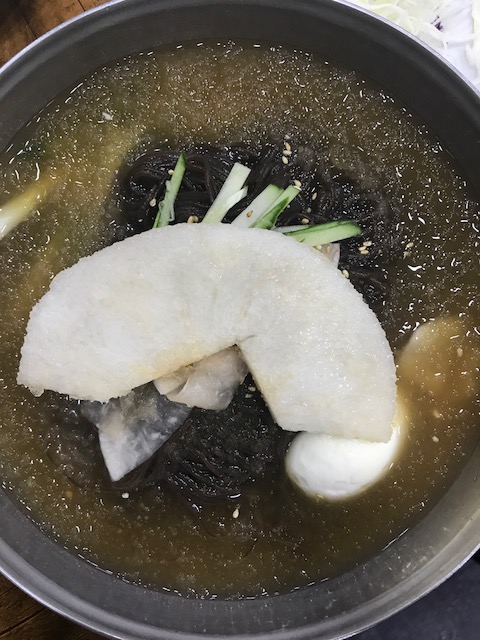

The Korean antidote to hot weather is (quite characteristically for people who believe that eating ginseng is good for you) consuming even more hot food. This is why we ended up at Gobong Samgyetang in the mall (it has a Michelin star don’t you know) ingesting hot chicken-ginseng soup at midday. The samgyetang features a whole chicken — not post-steroid Ben Affleck-sized, but juvenile-sized — stuffed with rice and ginseng, boiled and served in its own broth with dates and a smattering of sliced leeks and black sesame seeds. Served with a side of pickles, kimchi, and a “bone bucket” into which to throw your discards, it is both delicious and sweat-inducing. On weekends, Gobong only serves either sanghwang or hanbang samgyetang (with added medicinal herbs). This one-pot meal is considered a summertime go-to.

Hanbang samgyetang at Gobong

If chicken stew is meant to improve your stamina, I guess even more stew could turn you into Wonder Woman. With this in mind, our friends took us to get kimchi jjigae (kimchi hotpot) at a convivial, buzzy restaurant where everything was in Korean, including the name. Everyone was thoughtfully given bibs to wear, but the cooler, in-the-know Koreans simply draped these bibs over their laps, because unlike me, they wouldn’t be sloshing their grody kimchi juices everywhere. This stew was served with sides of cold soup and dried seaweed, as well as chilled guava juice, all meant to lessen the sting of the spice. Koreans seem more thoughtful about this than the Thais, whose anti-spice remedies amount to laughing at you, cucumbers, and rice.

Kimchi stew with a side of cold soup to alleviate the spice

Such is our love for chicken that we even made time to trek two hours out of town (on three different trains) to Chuncheon, where a street crowned with a giant golden rooster is lined with myriad restaurants all serving the same dish: dak galbi, or chicken stir-fried on a hot plate.

Dak galbi, at the most popular place on the strip

Our friend Michelle tells us that dak galbi was a dish favored by poor students who dreamed of dining on real galbi made from red meat, but could only afford chicken. So the dish was rebranded as galbi, although it in no way involves “ribs”. Our host Jay ordered two servings of intestine to go with the chicken, probably because he was punking us. Not surprisingly, this stirfry — chicken, intestines, cabbage, scallions, onions et al — are wrapped in lettuce leaves and eaten with your choice of sauce, kimchi and raw garlic, if you like.

Incidentally, that is also the way we ate our Northern Chinese-style lamb kebabs, skewered and cooked in front of us at the table and later dipped into spices like dried chili and fennel seed while still dripping with fat:

Lamb kebab, with spices

Of course, no trip to Seoul would be complete (for a Thai, at least) without some Korean “barbecue”. Our hosts ordered us both pork and chicken, plus copious amounts of soju (distilled rice liquor) and enough kimchi to sink a dinghy, but before embarking on dinner we had to pass the test of the complimentary appetizers: a mound of Jay’s fave, black beef tripe, accompanied by pickled perilla leaves and several cubes of raw liver.

There is not much I can tell you about this except that it tastes exactly like it looks. I preferred the liver cubes seared, wrapped in fresh perilla leaves with a nice big dab of ssamjang (brown dipping sauce). The soju didn’t hurt either.